* I started writing this last fall, when I was reading about the Spanish influenza pandemic — its genetics were similar to last year’s strain. And, like the Spanish flu (deadliest in people ages 20-40), last year’s flu mostly killed younger adults. The reasons for this are unclear — it may be because older people have been exposed to similar strains and school-age children have been vaccinated, while younger adults tend to think flu can’t happen to me, or that flu shots don’t work (or that the flu shot “gives” you the flu), or that they’re too busy.

Flu season always reminds me of Seady (Childs) Duckett (1878-1918). She died Sunday, 25 October 1918, just after the Arkansas-wide quarantine was lifted and on the first day church services were permitted to resume (Sundays only). She was 40. Her youngest daughter Bonnie was eleven and a half — just a little younger than my daughter is now. Seady is the woman in the middle, holding her new granddaughter, in this photo. Bonnie is standing off to one side.

Top Row L-R: Ola, Allen, John Owen Sr., Alma (Duckett) Owen. Bottom Row L-R: Selma Duckett, Seady (Childs) Duckett holding Lavelle, Ottie, Bonnie. Courtesy Clara Lou Queen Owen. Likely late summer 1917 or spring 1918.

Bonnie (Duckett) Robertson (1907-1989) told my mother this about her parents: Selma Duckett lived on the “home” place more than 80 years, from the time he was 4. All their children were born there. He was a road overseer for many years, employing and taking care of the payroll for labor and teams to do road work. He owned and operated a blacksmith shop and he farmed. He was also a member of the Duckett school board.

Selma used his blacksmith tools to shoe horses, to sharpen plows, and to make coffins for the dead of the surrounding community. Seady carded the cotton bats and lined the coffins with them. They did this as a service to the community. These people were buried in the Duckett Cemetery, which was located on Duckett property. Selma, Seady, and Mellie would travel for miles on horseback or on foot to take care of the sick.

Again according to Bonnie, “When Seady Duckett died, everyone was afraid to go to [their] home because everyone was sick with flu. Grandpa Duckett made caskets but bought one for Grandma Duckett.”

The Spanish flu hit the United States hard. Ten times as many Americans died of the flu as died in World War I. (And, half of the American soldiers’ deaths overseas were from influenza.) It killed so many young people that the US’s average life span was shortened by ten years. These deaths of America’s young people (675,000 men and women) were a loss of the future — comparable to the Civil War losses (620,000 men) less than sixty years earlier.

According to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas’ article, Flu Epidemic of 1918:

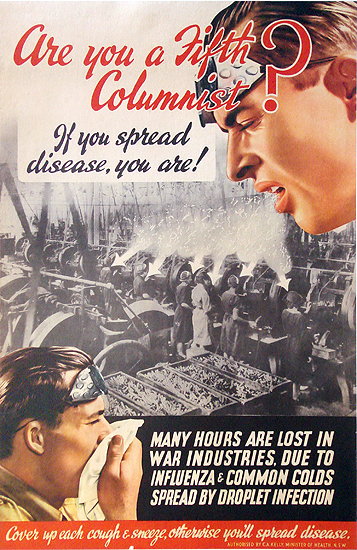

When the state confirmed 1,800 cases of influenza in October 1918, the Arkansas Board of Health put the state under quarantine, despite [U.S. Public Health Service officer for Arkansas] Geiger’s** continued reassurances (“Situation still well in hand”) and helpful hints (“Cover up each cough and sneeze; if you don’t you’ll spread disease”). Pulaski County lifted the quarantine on November 4, 1918, with county boards of health responsible for lifting restrictions in rural areas, though public schools remained closed statewide, and Arkansas children under eighteen were confined to their homes for another month.

The word influenza came from the Italian into English in 1743, when people believed that the stars “influenced” the course of disease. We know better now.

We know that flu is caused by an influenza virus, and that flu vaccines reduce the likelihood of you getting flu (and reduce serious outcomes if you do get the flu), and reduce the spread of flu to others. We know that you don’t get flu from the vaccine (although the vaccine doesn’t take effect immediately). We know that vaccines don’t work for everybody — some people can’t be vaccinated and some people don’t develop the antibodies. (For instance, my rubella (aka German measles) vaccine doesn’t seem to stick. I’ve been vaccinated several times, but my antigen levels don’t show it. I am grateful to all those around me who have also been vaccinated for rubella — for that reduces my chances that I get rubella or that I would have exposed my daughter to it in utero.) We also know that it’s still hard to predict who will die from flu and who will barely miss a beat — although it is absolutely true that people still die from the flu in the United States. (More than 48,000 people died from the flu in 2003-04.)

In a day and time that we have safe and effective vaccines, everyone in my family gets one — why wouldn’t I want to reduce the risk of leaving my daughter motherless or my mother daughterless? And, as much as I loved the pine box my husband made for my father’s ashes, I don’t think he wants to be put in the position of deciding whether he can bear to make a box for me any time soon.

Besides the references linked to above, I also drew from an excellent and readable article about the Spanish flu’s impact in Arkansas, Plague on the Homefront: Arkansas and the Great Influenza Epidemic of 1918, The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Winter 1988), pp. 311-344.

If you want to read some contemporary accounts, click through to the 8 Oct. 1918 Tulsa Daily World (8 Oct 1918) quarantine story, the 31 Oct. 1918 Hayti (Mo.) Herald mention of awaiting a niece’s body at the train station, or the 25 Oct. 1918 Williams (Ariz.) News asking that you lay aside clothes for influenza orphans along with a half dozen or more other stories about influenza. (Or, just go to the Library of Congress’ database of newspapers and search for Spanish influenza, between 1918-1919.)

** Geiger and his wife both eventually came down with influenza and his wife died of it.