When I was in grade school, I devoured the Little House books. Laura (Ingalls) Wilder lived in Indian Territory, not too far from where I grew up. When she had the fever and ague, Dr. Tanner, who saved her, was from Bartlesville. I’ve been to the cemetery where he buried some of his failures. And, of course, I knew about the Oklahoma Land Rush. I was fascinated by the idea of homesteading – that anyone over 21 could stake a claim, pay a total of $18, live on the land and improve and cultivate it for five years, and eventually have “free” land.

In graduate school, I learned about the 1862 Morrill Act, which is the foundational legislation for the land grant university system. Senator Justin Smith Morrill (1810-1898) (the uncle of my five-times-great-grandmother on my Yankee side) was responsible for getting that legislation enacted. I am still fascinated by the creative thinking (and how they had to wait until the Civil War to actually pass the bill).

Backing up, my grandmother Floy (Turrentine) Childs must have known I was reading the Little House books for one day she wrote a letter telling a story about some of her own relatives that were homesteaders. I remember sitting at the dining room table, and my mother reading the letter to us.

The way I remember the story, her grandfather Thomas Brock (1823-1908) had three siblings, Lucinda, Lawrence and Permelia, who decided to homestead together in Polk County, Arkansas. (Thomas also homesteaded in Polk County and would eventually be my great-great-grandfather.)

Lucinda, Lawrence and Permelia never married, so they found three pieces of land (each a quarter of a section or 160 acres) that adjoined each other and built one house where the properties intersected, and took up housekeeping together. In due course, they proved up their claims and owned their land free and clear.

As an aside, the three Brock siblings are not only great-aunts and great-uncle to my grandmother Floy, they are also kin to the Ducketts in at least two ways: (1) first cousins to Allen Turner Duckett and (2) first cousins once removed to Turner’s second wife (Sarah Drusilla Brock).

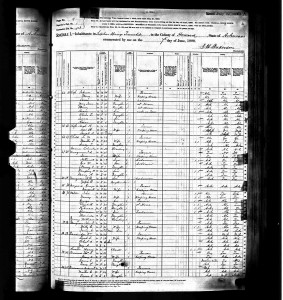

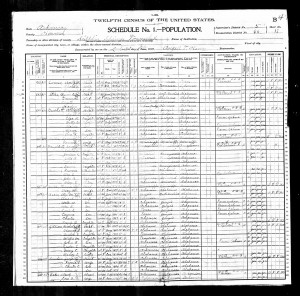

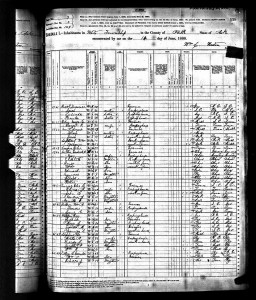

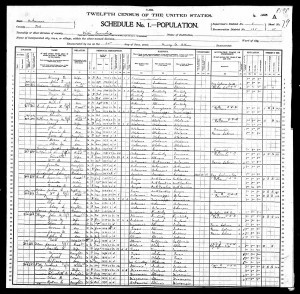

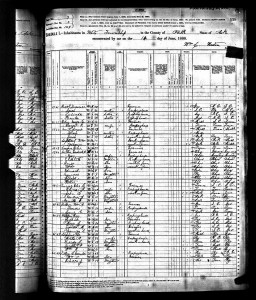

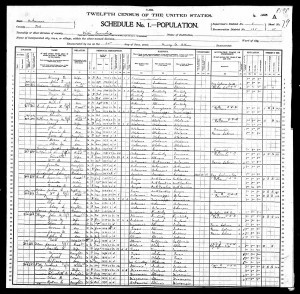

The 1880 and 1900 Censuses

The 1880 and 1900 censuses support this story. In the 1880 census, the three of them live together with their mother Sarah (Anderson) Brock (who died in 1884 at the age of 86). The 1900 census also shows the three of them living together: Lawrence Brock, head, born July 1840; Lucinda, sister, born September 1835; Permelia, sister, born May 1842, and Joshua D. Holden, nephew, born May 1854. The Brocks were born in Georgia, their father in North Carolina and their mother in South Carolina. Joshua (son of their sister Mary (Brock) Holden) was born in Texas, his mother in South Carolina and his father in Georgia.

As is often the case with family stories, the story is both true and untrue. Their homesteads did abut each other, and I think they did live together, but they had to build three houses, one on each homestead, before they could prove their claims.

The Land Grant Files

From the land grant applications, Lucinda’s father John and brother (probably Lawrence, but Thomas could have helped) built the first house in 1877 – which was on the land that Lucinda homesteaded. (John was 75 when they built or bought the 1877 house.)

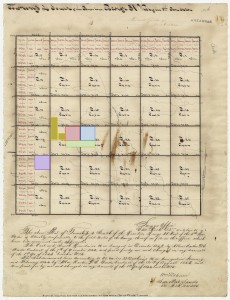

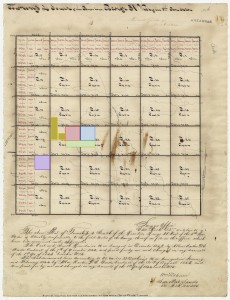

Permelia Brock’s land is in green, Lucinda Brock’s land in red, and Lawrence Brock’s in blue. The purple was homesteaded by their brother Thomas. The yellow was John D. Towry’s homestead.

Lucinda & Permelia

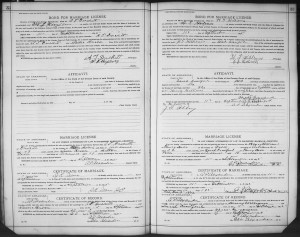

Lucinda and Permelia both submitted their Homestead Applications in Camden, Arkansas, along with $14.00, on October 19, 1882. Lucinda and Permelia published Legal Notices in the Dallas [Polk County] Courier from February 1889 to March 1889, and listed George C. Miller, John D. Towry, John E. McBreom, and Charles M. Miller, all of Cove, as potential witnesses. Their testifying witnesses were John D Towry and George C Miller. However, the testimony for Lucinda and Permelia diverged.

Lucinda

Lucinda’s application proceeded smoothly.

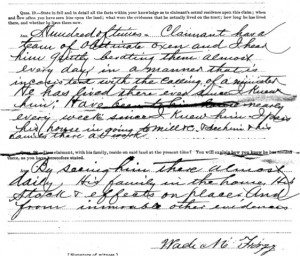

John D Towry, their neighbor and cousin by marriage,* submitted testimony on Lucinda’s behalf on March 30, 1889 in Dallas (then the Polk County Seat**). He was 40, and said he frequently saw her on the land.

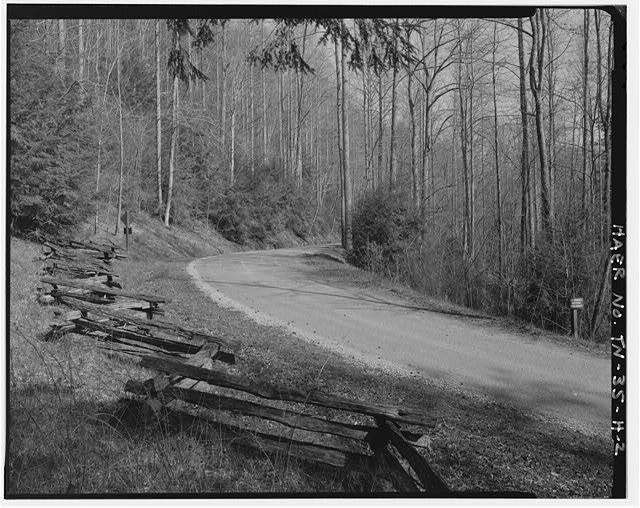

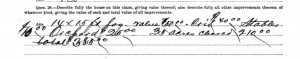

Lucinda had lived on the land since 1877, according to Towry. The improvements consisted of a dwelling house with 2 rooms and gallery (valued about $100), a smoke house, kitchen, and 4 acres in cultivation. Her house was 18×32 feet, constructed of “logs and lumber and habitable all seasons of the year.” Towry said there was four acres broken and plowed, and put in crops each season, including corn, wheat and cotton. Total value $240 in improvements and $440 in land. George C Miller, another nearby homesteader aged 45, and Lucinda herself gave similar testimony.

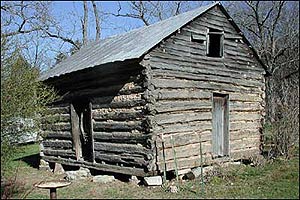

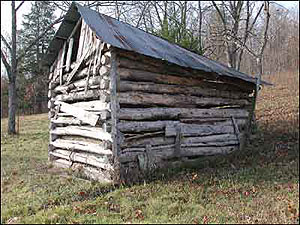

I suspect that the house was initially a single pen log cabin, about 16×18 feet, with a second cabin subsequently built with a gallery or dog trot in between. This photo, of a dog trot cabin built between 1866 and 1879 and surveyed in 1979, seems to me to be a pretty good example of a house built of “logs and lumber.” The survey measures the rooms’ interiors at just about 17′x17′, with an eight-foot wide dog trot between the rooms.

Log cabins were built in modules, and were limited in size by the size of logs a man could conveniently haul and stack. Around here, as in this Mississippi example, the logs were usually planked, or flat, on both the inside and outside of the house. (They did not look like Lincoln Logs, in other words.) You would put chinking in between the logs to reduce drafts. The kitchen was separated from the house to keep the house cooler in the summer and reduce the risk of house fires.

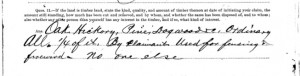

Lucinda described her land: “timber consisting of pine, oak, hickory, etc.” She went on to describe the details of her living arrangements: “In the year 1877, my father bought the improvements and moved on this claim and I was living with [him] and moved on this claim with him. He paid about settled the place.” (Strike outs in original.) “The land was not occupied by any person when I moved on this claim.” “My house was built by my father and brother in the year 1877 & the same is habitable all seasons of the year.”"I have no family of my own but live with my bro[ther] and sister – all of us being unmarried.”

Lucinda listed farm implements: plows, hoes, axes, etc. She also kept three head cattle and poultry. Her furniture included a bedstead, table and chairs.

Lucinda obtained her patent on April 24, 1890, about a year after she made her final payment.

Permelia

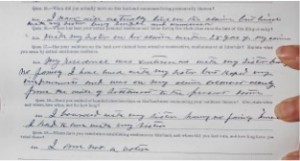

Permelia’s application did not go as well. She established that she had cleared the land and made the required improvements by March 1889, but initially failed to prove that she had actually made a home on the claim. The testimony (including her own) was that she lived within 25 yards of the claim — but she and her testifying witnesses tried unsuccessfully to excuse it by virtue of the sisters being “single and unmarried.”

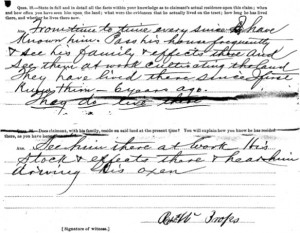

John D. Towry testified that he had been to the land “too often to recollect” and had last seen her on the land about ten days ago. The improvements “consist of [illiegible] garden orchard” with about 16 acres in cultivation (in contrast to the four acres cleared on Lucinda’s claim). The 16 acres had been broken, and plowed and put in crops. She raised “corn, wheat, oats, and cotton,” and had raised a crop every year. He testified that she had “no resident house in the claim but lives with her sister, both being single and unmarried.” She and her sister lived within 25 yards of the claim.

George C. Miller also testified. He had seen her often on the land, as recently as a month ago. Like John D. Towry, he explained that she lived with her sister, “being single and unmarried” but within 25 yards of her claim, and said she worked on the claim “all the time.”

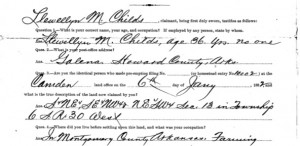

Permelia submitted her own testimony. She was 41, and a farmer in her own employ. Before she settled on the land, she lived in Polk County and was a farmer. She described the land, “The land is timber consisting of pine, oak, hickory, etc. and at date of entry there was … 152 [acres] standing in timber and at this date 144 acres in timber. There has been no timber cut except what has been done in improving the place.” (Doing the math: eight acres were cleared before she filed her application, and another eight acres cleared over the next six years.)

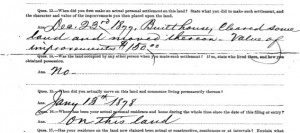

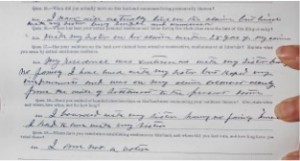

As for the improvements,

- “My father bought the improvements [possibly referring to the cleared land or to the improvements on her sister's place] about 14 years ago and I was living with him.”

- “I never did actually live on the claim but lived with my sister being single and unmarried.”

- “My residence was continuous with my sister. Having no family, I have lived with my sister, but [illegible]ed my improvements and was on my claim almost daily from the date of settlement to the present time.”

- “I boarded with my sister, having no family home I had to live with my sister.”

- “I am not a voter.”

- “I have no family. Being a lone woman, I could not conveniently live on my claim.”

- “The improvements consist of stable, gardens, orchard.”

- “I … keep on the claim plows, hoes, axes etc.”

- “I own and keep on the place, 1 horse, 3 head cattle, poultry etc.”

(Note the similarity in improvements, farm implements, and livestock between Lucinda and Permelia.)

Apparently (for the file is silent on this point), the federal government required her to build a house and live in it for five years, no matter how inconvenient it may have been for a single woman.

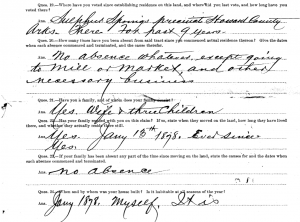

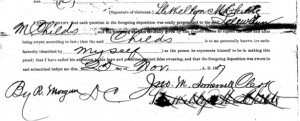

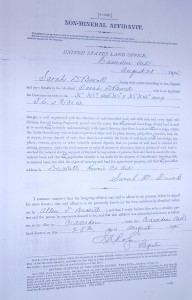

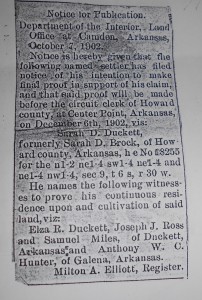

On January 7, 1898, she submitted testimony that she built a dwelling house in October 1892, “and moved on the land and established actual residence thereon and have continued to reside on the same to the present time. So help me, God.” Her nephew Joshua B. Holden (the same nephew that was living with them according to the 1880 census) and another probable relative William J. Towry corroborated her testimony. (I’m not sure who William J. Towry is.) This testimony satisfied the requirements and she was awarded her grant on June 23, 1898, twenty-one years after her family moved to Polk County, fifteen years after she filed her claim, and six months before Senator Morrill died (36 years after the act bearing his name passed).

Lawrence

Their brother Lawrence (or Lawrance with an ‘a’ as it is spelled throughout his file) waited to submit his homestead application until March 13, 1895 – 13 years after his sisters first submitted theirs. He submitted it at the county seat, Dallas, rather than traveling to Camden, “by reason of distance and expense.” (Interestingly, his niece Sarah Brock went to Camden with her future husband Turner Duckett just five months later to submit her application in person.) The 1897 forms were shorter and less informative than the earlier forms.

Lawrence ran his Legal Notice in the Mena Democrat from July-September 1897. His proposed witnesses were: Thomas Stephens, John C. Towry, Henry D. McDaniel, and William I. Towry, all of Janssen, Arkansas (later renamed Vandervoort).** His testifying witnesses were Henry D. McDaniel and John C. Towry (not the John. D. Towry that testified for his sisters).

John C. Towry, age 31, testified in September 1897 that Lawrence moved onto the land in March 1892, seven months before Permelia’s cabin was built in October 1892, and three years before he filed his homestead application. Lawrence “is single and unmarried but has resided continuously on the land since settlement.” He had “a dwelling house, out buildings, and about 35 acres in cultivation, value about $500.” Henry D. McDaniel, age 35, testified similarly.

In September 1897, Lawrence testified that he was 57 years old and ”borned” in Georgia. ”In March 1892, I built a house on this land and moved on it and established residence therein. I have dwelling house, out buildings, garden, orchard etc. and about 15 acres in cultivation, $500.” My family consists “of myself only and I have lived continuously on this land ever since settlement. I am single and unmarried.” He received his grant on December 10, 1897, about twenty years after his father built the first cabin on what was to become Lucinda’s homestead – not exactly a fast path to home ownership.

+ If you were at the Duckett-Childs Family Reunion this June, this may sound familiar to you since I presented much of the information there.

*John D. Towry’s first cousin, Mary Jane Towry, married the siblings’ brother Thomas Brock in 1865. Thomas and Mary Jane (Towry) Brock were the parents of Sarah Drusilla (Turner Duckett’s second wife) and Eliza Permelia (Floy’s mother) among others. John D. Towry also homesteaded in Polk County, being awarded his claim on November 15, 1894.

** Dallas had the first Polk County courthouse. It burned twice, once before 1869 and then again in 1883. The county seat relocated to Mena in 1898. Janssen was renamed Vandervoort by a man who worked for the founder of the Kansas City Southern Railroad. Actually, he named the town Janssen, and then renamed it Vandervoort: Janssen for his wife’s maiden name, and Vandervoort for his mother’s maiden name. See the Encyclopedia of Arkansas entry on Polk County.